PM Johnson’s promise to “Get Brexit Done” was a powerful slogan for the election and gifted him a landslide victory and a large parliamentary majority of 80. That means that he will almost certainly win a vote in Parliament on his version of the EU Withdrawal Agreement. Then, the UK will formally leave the EU in January 2020. Brexit will be implemented within a transition period during which rules and regulations remain aligned with the EU.

The transition period ends in December 2020, according to the Withdrawal Agreement, and PM Johnson has committed not to extend it. However, a trade deal with the EU will likely be even more difficult to negotiate than the Withdrawal Agreement and could easily drag on well beyond the December 2020 deadline he has set.

The UK and EU only have until the summer to strike a deal that can be implemented by the end of 2020 or to seek an extension of the transition period, if no trade agreement is ready. This is because formal ratification of EU trade deals requires over four months of legal checks and translation.

With this in mind, we consider three scenarios: first, a rapid trade deal; second, an extension of the transition arrangement and third, a hard no-trade-deal Brexit.

PM Johnson claims a rapid trade deal will be easy because the starting point is full alignment of UK and EU regulations. However, it is clear that PM Johnson wants the UK to diverge from EU regulations and standards. For example, he has said the UK would deviate from EU state aid rules to make it easier to prop up ailing industries. This would clearly distort the “level playing field” that the EU insists upon in trade negotiations with other countries.

Hence, we do not believe that the EU will agree to the UK having autonomy regarding on state aid, labour law, the environment, tax and migration policy, whilst retaining full access to the EU market.

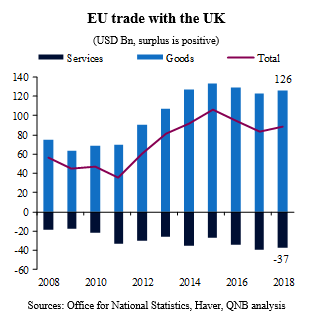

The EU has a large surplus in goods trade with the UK (USD 126 Bn in 2018). So, it is no surprise that the EU’s chief negotiator, Michel Barnier, has said that his objective will be to strike a deal, which provides tariff-free and quota-free trade in goods. However, the EU has had a persistent deficit in services trade with the UK (USD -37 Bn in 2018). Indeed, the City of London has historically provided financial and professional services seamlessly to other EU countries. International trade agreements tend to achieve less in terms of market access for trade in services than they do for goods. It is also already clear that other European capitals are already pitching hard to attract business away from London.

Next, we consider the possibility that the UK and EU are unable to make a trade deal and instead agree on an extension of the transition arrangement. PM Johnson explicitly promised not to do this in his election manifesto. This was likely to secure the votes of people who favour a hard Brexit in the election. However, he has reneged on numerous previous promises and we see this as the most likely scenario for two reasons. First, the Withdrawal Agreement already makes provision for a potential extension until 2022. Second, PM Johnson’s large parliamentary majority protects him from supporters of a hard Brexit within his own party, who could try to topple him with a leadership challenge.

Finally, we consider the possibility that no-trade-deal is agreed before the end of 2020 and PM Johnson sticks to his promise not to extend the transition period. This outcome is effectively the same as the No-Deal Brexit we have written about before. After the transition period ends, the UK would begin 2021 trading with the EU with new trade barriers, quotas and tariffs set according to basic WTO rules. PM Johnson has avoided talking about this possibility by simply insisting a deal would be done.

In conclusion, we judge the most likely scenario is an extension of the transition arrangement. The above challenges mean that a rapid trade deal is unlikely and allowing transition arrangement to end in 2020 with no-trade-deal would be a severe and unnecessary shock to the UK economy. Therefore, Brexit-related uncertainty is likely to persist into 2020 and beyond. However, PMs Johnson’s large parliamentary majority will allow him to take policy measures to stimulate the UK economy and offset some of the headwind from persistent uncertainty. In particular, near zero borrowing costs mean that the UK government can afford to borrow billions of pounds to spend an invest in support of UK economic growth.

Download the PDF version of this weekly commentary in English or عربي