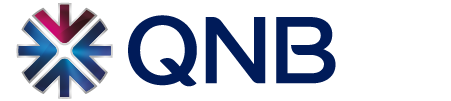

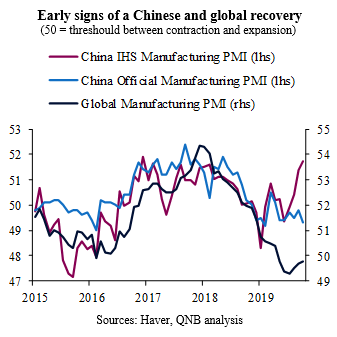

After several months in the doldrums, global manufacturing demand started to point to a potential rebound in the coming months. This will likely create a moderate acceleration of headline global GDP growth in 2020. The pace of the recovery, however, is to a large extent dependent on China’s economic performance. The last periods of industrial recovery were amplified by major tailwinds produced by policy stimulus in China. In fact, over the last decade, bouts of more accommodative monetary and fiscal policies in China produced “reflations” that spilled over to commodity prices, emerging markets and other open economies, supporting synchronized global growth mini-cycles. Given all of the above, policymakers and investors are questioning whether 2020-21 will repeat another manufacturing/China-induced mini-boom.

While we believe a recovery in global growth is going to take place in 2020, the upswing is expected to be more moderate than in 2016-17. This is mostly due to the idiosynchratic Chinese situation. Despite sound signs of growth stabilization in China, a stronger recovery will likely be contained by a rather modest cycle of policy stimulus. In our view, three main factors are limiting a stronger policy response from Beijing to the recent slowdown.

First, after several bouts of debt-fuelled economic stimulus, Chinese authorities want to avoid another major phase of debt accumulation. In other words, the government does not want short-term stimulus to undermine long-term financial stability. Economic authorities have been trying to rein in excessive credit growth and cut debt levels, de-coupling growth from credit intensive activities. This is why regulatory controls to limit off balance-sheet or shadow bank lending are still in place. Such commitment naturally puts a cap on potential stimulative policy measures. The government will not radically change course unless the slowdown returns to threat a “hard landing,” i.e., a disruptive recession. As the economy appears set to recover modestly and trade conflicts recede, there is no immediate need to unlock the stimulus “bazooka” at this juncture.

Second, continuous uncertainty and the ebbs and flows of trade conflicts with the US begets caution in Beijing. The Chinese government wants to be prudent and save policy space/stimulus ammunition in case trade negotiations turn sour or exogeneous shocks hit.

Third, cross-currents in prices are also limiting a further easing of monetary policy. While weaker growth has produced deflationary pressures on producer prices, external supply shocks such as the African Swine Flu pushed up the headline consumer price index (CPI) to 3.7% year-on-year (y/y) in October. This is considerably above the 3% policy target/ceiling for the year. Food prices are up 16% y/y, driven by a surge in meat, poltry and related products. Food supply headwinds are expected to persist, placing additional pressure on the CPI. Because of potential negative effects of a high headline CPI figure on inflation expectations, the People’s Bank of China is set to procede with a rather cautious stimulus.

All in all, Chinese authorities are expected to continue to ease policy and support growth. However, policy measures will likely be more contained than in previous cycles. Therefore, sequential GDP growth should recover only gradually from a bottom of 5.3-5.4% in Q3 and Q4 2019. For the full year in 2020, economic authorities are expected to achieve their target of around 6% growth.

Download the PDF version of this weekly commentary in English or عربي