In June 2019, we noted that Brexit uncertainty has been a persistent drag on the UK economy since the June 2016 referendum when the UK narrowly voted to “Leave” the EU rather than “Remain” in the EU. In that article we and anticipated that a general election, or second referendum, would be necessary.

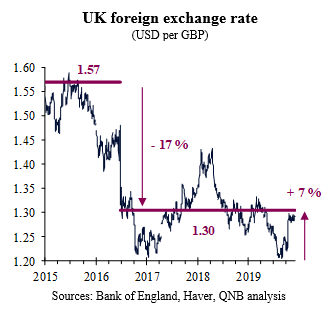

The outlook for economic growth is one of the main determinants of the strength of a currency. The British pound (GBP) fell sharply after the 2016 referendum and remains 17% below the average of the previous 5 years (see Chart). This illustrates the market concern about the negative impact of Brexit on the outlook for the UK economy.

Since our last article, Boris Johnson has taken over as the British Prime Minister (PM) and renegotiated the deal with the EU on the Withdrawal Agreement. However, he was unable to push it through the British Parliament by the 31 October deadline. After losing numerous votes in Parliament, PM Johnson was forced to request a further extension of the Brexit deadline to the 31 January 2020.

The hardest form that Brexit could take is often referred to as “No-deal”, whereas remaining in the EU is effectively the softest form of Brexit. PM Johnson’s deal with the EU on the Withdrawal Agreement implies a harder Brexit than most of the options being considered during the summer of 2019.

That alone would imply a weaker outlook for the UK economy and British currency (GBP). However, GBP has rallied 7% since early October 2019 when PM Johnson failed to push his deal through Parliament and called a general election to be held on the 12 December 2019. In our view, much of the “No-deal” tail risk was priced out of both FX spot and options markets.

The Conservatives and Labour parties have dominated British politics for many years. However, fractures into “Leave” and “Remain” camps run through both main parties, making future voting patterns less predictable than ever. The main parties have different views for Brexit. So we consider three scenarios.

First, if a Conservative government were to be elected with a workable majority, then Brexit would move forward faster, with PM Johnson’s deal likely to be passed soon after the election.

Second, if a Labour government came to power, then PM Corbyn would attempt to renegotiate a new Withdrawal Agreement. He would then call for a second referendum, which would prolong uncertainty but also open up a path to “Remain”.

Third, the election may result in a hung parliament or weak minority government, barely able to forge a coalition. While this would raise the possibility of a second referendum, it could also bring “No-deal” back on the table and prolong uncertainty.

Back in June, opinion polls suggested that a general election would lead to a hung parliament with Labour as the largest party. However, the most recent opinion polls are indicating a clear majority for the Conservatives. Indeed, the latest prediction by pollster YouGov is that the Conservative party would win 359 seats and deliver PM Johnson a working majority of 68.

PM Johnson’s promise to “Get Brexit Done” is a powerful slogan for the election. However, a trade deal with the EU could not be discussed before the a Withdrawal Agreement is implemented and will likely be even more difficult to negotiate. Therefore trade negotiations and Brexit uncertainty are likely to drag on well beyond the December 2020 deadline set by PM Johnson in all three scenarios.

Download the PDF version of this weekly commentary in English or عربي